Welcome to this week’s Deep-fried Dive with Fry Guy! In these long-form articles, Fry Guy conducts an in-depth analysis of a cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) development or developer. Today, Fry Guy is exploring how a “stolen” piece of AI art was sold for $432,500. We hope you enjoy!

*Notice: We do not gain any monetary compensation from the people and projects we feature in the Sunday Deep-fried Dives with Fry Guy. We explore these projects and developers solely for the purpose of revealing to you interesting and cutting-edge AI projects, developers, and uses.*

🤯 MYSTERY LINK 🤯

(The mystery link can lead to ANYTHING AI related. Tools, memes, and more…)

A few years ago, many in the art world believed that an AI “art heist” went down, and in the wake of increasing AI creativity, the underlying issues of this event are beginning to resurface.

As AI-generated art first began to burst onto the scene, one 19-year-old’s code was cloned by an art collective and used to create a piece that sold for over $400,000 at a prestigious auction. This 19-year-old coder was left in the dust, reaping not even a penny. Let’s explore how this all went down, and whether it truly was a massive AI art heist or just a big misunderstanding.

AN AI ART MASTERMIND

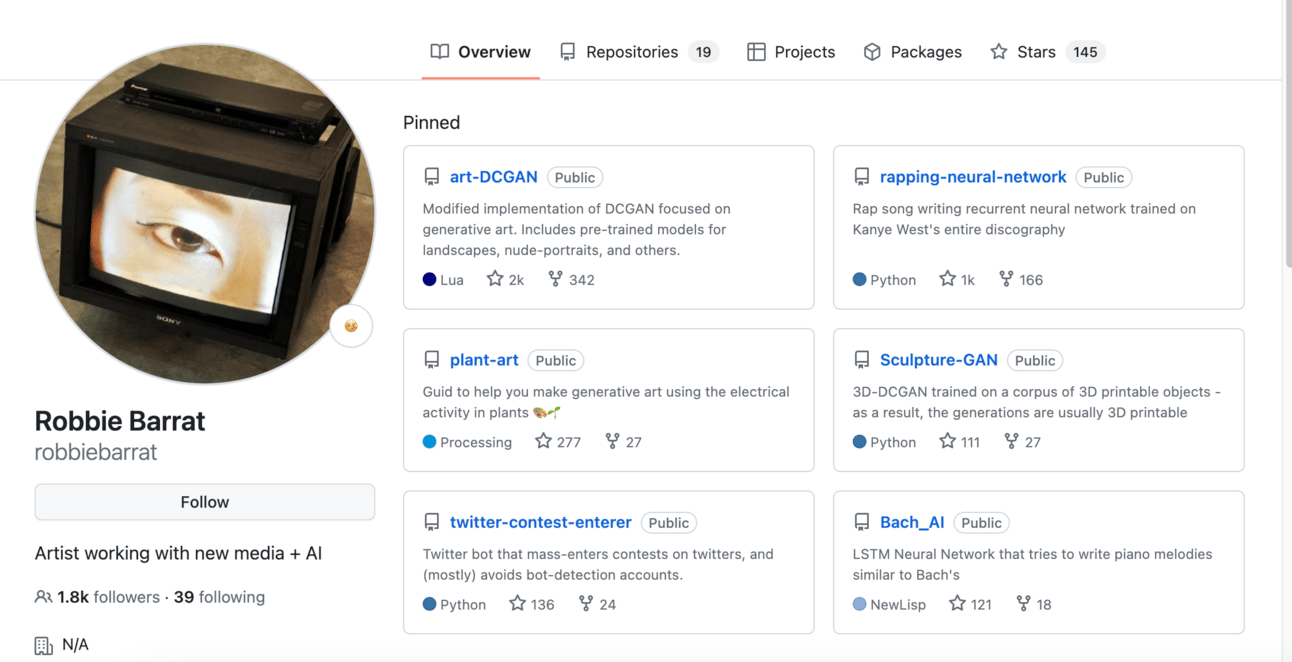

From a very young age, Robbie Barrat was fascinated by neural networks and machine learning for generating art, music, and other creative content. This passion for AI led him to publish thousands of lines of open-source AI code on Github. The code and subsequent projects ranged from generative AI artwork to generative AI rap songs.

One of the most incredible things about a 19-year-old doing all this work is that he was coding all of these projects years before ChatGPT was even available. At that time, there was little to no attention being given to AI, and many people didn’t see much potential in these sort of generative AI projects. However, that didn’t matter to Barrat—he followed his passion regardless.

One of Barrat’s most notable projects on Github is called DCGAN, which is a type of Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). In simpler terms, this is an AI model that scans datasets and looks for patterns. In the case of DCGAN, it scans famous artwork from the likes of Picasso, Monet, and Matisse, and then looks for patterns in this artwork. These patterns include, for example, identifying how the average person rendered in an artist’s painting in the 16th century might look. These patterns are then sent to a second model called a discriminator model, which compares the AI-generated pattern it received to a real world piece of artwork, like the Mona Lisa. If the model thinks the generated pattern is “real art,” then it will stop and generate the pattern image. If it doesn’t, the entire DCGAN model will start all over again in a looping process until it is satisfied. In this way, it functions basically a self-learning AI model.

Quickly after its creation, Barrat’s generative AI code started to gain attention within the AI art world, and it caught the eye of an art collective named “Obvious” out of France. At the time, this particular collective was comprised of three 25-year-olds who shared similar ideologies and art interests. Digital art blogger Jason Bailey described the group as a tech-focused collective that wanted to make a splash in the traditional art world. He stated, “Three 25-year-olds wanted to do something entrepreneurial and startup-y. They saw that AI was getting a lot of attention and grabbed some code.” And to Bailey’s point, the collective, in order to make a quick name for themselves, grabbed the code from Barrat’s repository and used it to create a piece of art called: “Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy.”

“Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy,” which is displayed in a gilded wooden frame, depicts a blurry and unfinished image of a man (the kind of thing art fanatics go crazy over). Hugo Caselles-Dupre describes how the Obvious collective created the painting by saying, “We fed the system with a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th century to the 20th,” and then the model tried to create its own. Obvious printed the image, framed it, and signed it with part of the GAN’s algorithm: “min G max D Ex[log(D(x))] + Ez[log(1-D(G(z)))].” The collective then put it up for auction at Christie’s, one of the most prestigious auction houses in the world.

“It may not have been painted by a man in a powdered wig, but it is exactly the kind of artwork we have been selling for 250 years.”

Christie’s is an auction house that has a proven track record of selling high-end art at astronomical prices. For instance, in 2017, they auctioned off the Salvator Mundi painting by Leonardo Da Vinci for $450 million. Before the bidding started on Obvious’ “Edmond de Belamy” portrait, the British auction house estimated that the AI piece would sell for around $7,000-$10,000. To the surprise of everyone, when the bids started rolling in, a bidding war ensued between five buyers and ended a short seven minutes later, with a winning bid of $432,500 by an anonymous phone buyer. This meant the piece sold for over 40 times its estimated value and sold for more than six times the value of an Andy Warhol piece that was auctioned off that very same day. This was the first AI-generated piece of art sold by the 252-year-old auction house and still remains the highest valued AI piece of art ever sold. This sale meant that AI art was setting a new precedent in the stagnant world of traditional art, and its potential for creativity was emerging.

A USEFUL RESOURCE OR A MAJOR HEIST?

Although the AI art made a huge splash at Christie’s, this landmark sale was just the beginning of the story. The backlash following this sale quickly became heated, and Barrat was left with years of work that landed him with empty pockets and no credit for his work. In the midst of his frustration, he tweeted, “Does anyone else care about this? Am I crazy for thinking that they really just used my network and are selling the results?” His long-developed code had been used by others for a massive reward, and he was truly left in the shadows. Mario Klingemann, a German artist who has won awards for his own work with GANs, told The Verge, “You could argue that probably 90 percent of the actual ‘work’ was done by [Barrat].” This raises questions about who truly deserves the credit.

The controversy of this AI art sale rippled throughout the art community for months, but the ethical weight remained surrounding whether or not the Obvious art collective who sold the work did anything wrong. Did they break any laws? Did they violate a usage policy? This is up for debate. Robbie Barrat’s code was—at the time and still is—open-source code, which means it can be reused in certain circumstances. If one looks at his code’s current license, however, there is the following disclaimer: “EXTRA: NO OUTPUTS OF THE PRE-TRAINED MODELS MAY BE SOLD OR USED FOR-PROFIT OTHERWISE.” The problem is, however, there’s no way to tell if the license said that when the “Edmond de Belamy” portrait was produced.

Some people don’t think it matters whether the production and sale of this art was legal or not because it was clearly unethical. For instance, Bailey wrote, “There’s a lot of stuff you can do that’s legal, but that makes you sort of a jerk. If I was Robbie, I’d be pretty miffed!” The only real way to find out the legality of the situation would be through court, if Barrat sued Obvious for stealing his work. But at this point in time, it doesn’t looks like that will happen, as Barrat has moved on with his life, though his open-source code remains available.

FAST FORWARD TO TODAY

Is creativity only for humans?

Beyond showcasing value at art auctions, AI art and images have taken the world by storm. Stable diffusion tools have quite literally taken over the internet, and tools like Midjourney and OpenAI’s DALL-E have been leading the way.

Years ago, AI art was thought of as a pathetic attempt to imitate humans. As German artist Klingemann said in reference to Obvious’ piece, “To me, this is dilettante’s work, the equivalent of a five-year-old’s scribbling that only parents can appreciate.” Given the rapid development of generative AI in the past two years, however, AI art now has the ability to captivate hearts and trick minds. And it isn’t only images, as AI has made its way into voice, music, videos, and more, revolutionizing the way we think about various art forms.

Even though things have changed since the Barrat case, the underlying question surrounding these creations remains: who gets the credit when things go right, and who gets the blame when things go wrong? This, like the Barrat controversy, is up for debate. What isn’t up for debate, however, is that it is no longer just humans who posses creative potential.