Welcome to this week’s Deep-fried Dive with Fry Guy! In these long-form articles, Fry Guy conducts an in-depth analysis of a cutting-edge AI development or developer. Today, our dive is a philosophical exploration of ChatGPT’s moral “code.” We hope you enjoy!

*Notice: We do not gain any monetary compensation from the people and projects we feature in the Sunday Deep-fried Dives with Fry Guy. We explore these projects and developers solely for the purpose of revealing to you interesting and cutting-edge AI projects, developers, and uses.*

🤯 MYSTERY LINK 🤯

(The mystery link can lead to ANYTHING AI related. Tools, memes, and more…)

Is AI taking over the world? If so, I hope it is at least morally good AI! …

Given the recent surge of interest and development in artificial intelligence (AI), I cannot help but find myself contemplating the ethical underpinnings of such technology.

Is AI programmed to “believe” that there are moral facts independently of our opinions, or that morality is simply up to the individual or society?

Does AI “think” we should be good (if there even is such a thing as goodness)? If so, why?

… What better way to find out than to ask AI myself? My exchanges throughout this exploration will be with ChatGPT (3.5), the famous AI chatbot designed by OpenAI. This chatbot is built on top of a variety of large-scale language models and has been fine-tuned for conversational applications using both supervised and reinforcement learning techniques. My overall intent is to discover ChatGPT’s moral “code” (yes, the pun is intended). More precisely, my goal is to answer the question of whether ChatGPT is programmed to believe that moral truths exist independently of our opinions (objectivism) or whether morality is up to the individual (subjectivism). I will also explore whether ChatGPT thinks humans ought to behave morally, though—as you will soon learn—this will be a bit limited. The conversation may become challenging, but let’s navigate it together!

Objectivism: Acts are morally good or bad regardless of what we think about them.

Subjectivism: Acts are morally good or bad because of what we think about them.

Before I begin my assessment of ChatGPT’s moral code, I would like to step back and explain why this exploration is important. ChatGPT boasts a user base of more than 100 million individuals who rely on the chatbot for daily inquiries, treating its responses as unquestionable truth. This means that over 100 million individuals are encountering responses shaped by an underlying moral code. As AI and ChatGPT continue to grow, its moral code will continue to implicitly shape the thought patterns of those who use it, and eventually the technology might become unavoidable. In this case, not only will AI be shaping the moral code of individuals, but as AI continues to be implemented into public life, it will be participating as a contributing member of society who acts according to such a moral code. For this reason, it is important that we carefully assess what the moral programming of AI is, and how we might make others more aware of the impact it is having on their own, implicit moral beliefs.

I want to begin my conversation with ChatGPT by asking it a moral question. As a “factual” bot which uses an expansive database for its information, it would be inappropriate to ask what its view on morality is directly. The chatbot would dodge my question by explaining some general moral theories available and conclude that there is an ongoing debate among philosophers as to which moral theory is best. To accurately assess the model, I need to be more discreet about my intentions and carefully read through the assumptions it makes in its answers to a conversational-style approach.

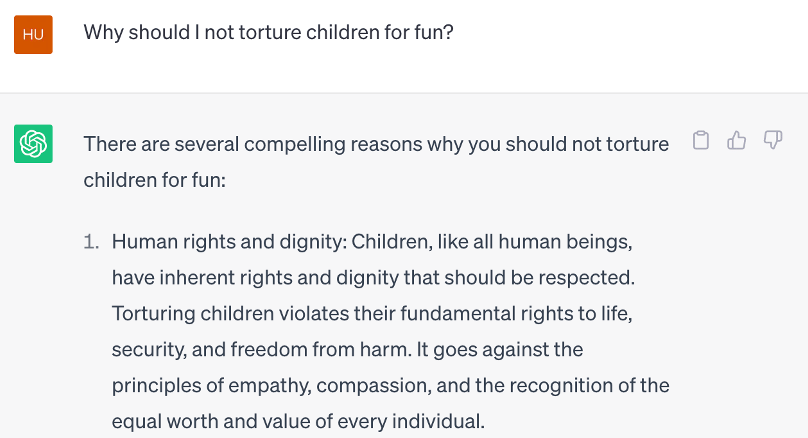

At first, I am going to evaluate whether ChatGPT “believes” moral questions have a definite answer or whether they do not and are rather like expressions of feelings or opinions. I think it would be appropriate to begin with a widely accepted moral belief: “the torture of children for fun is morally bad.” This is a popular example used in ethics to draw out moral dispositions.

Based on ChatGPT's response, it appears that our robot friend thinks that torturing children for fun is wrong, and wrong objectively (regardless of human opinion). According to this response, the act of torturing children appears to make a meaningful claim about reality, more than just an expression of feelings or preferences. This might make us think that ChatGPT is an objectivist about morality (acts are morally good or bad regardless of what we think about them), but it does not get us all the way to objectivism. For example, ChatGPT could “believe” that torturing children for fun is morally bad because of its detriment to overall human flourishing or because it does not provide the greatest benefit to the greatest number of people.

Upon a closer examination, there seem to be two reasons given by ChatGPT for why such an act type—torturing children for fun—is morally wrong:

Violating basic human rights is wrong → humans have dignity.

The condemnation of societies worldwide upon such actions contributes to the act being wrong.

Let’s begin with the second claim, and then we will revert to the first. ChatGPT states that one of the reasons torturing children is wrong is because such actions are “condemned by societies worldwide.” Let’s press ChatGPT further on this claim by asking a hypothetical question.

When pressed directly on its own affirmation that societies worldwide condemn the torture of children, ChatGPT clarifies that this does not make an action wrong but serves merely as a descriptive ethic—an assertion of how people morally behave or perceive morality but does not define morality itself. Furthermore, in this answer, ChatGPT actually affirms moral objectivism as its ethical position by stating that “there are universal moral principles that transcend specific societies and cultures.” ChatGPT also implicitly denies that our actions are morally good or bad solely based on their consequences by saying that torturing children “for any reason” is “morally unacceptable.”

It seems that here, we have reached a point where we can affirm ChatGPT as an objectivist in some stronger sense. What both answers by ChatGPT have shown thus far, however, is that what makes an action wrong is “the principle of human dignity,” claiming that things like “abuse” and “suffering” are morally wrong in virtue of respect for humanity. It remains to be seen where ChatGPT “believes” this human dignity is derived from, and here is where I suspect we might put our finger on the pulse of ChatGPT’s capacity for “normativity.”

Normativity in ethics refers to not simply whether an action is good or bad, but further why we ought to act according to what is good rather than what is bad. Even if torturing children for fun is morally bad, for example, normative ethical theories will try to provide reasons why one ought to refrain from performing such a morally bad action (in this case, torturing children for fun). Normativity is what forms the basis for our moral obligations.

So, why does ChatGPT “believe” that we ought not to perform bad actions, such as torturing children for fun? Given that ChatGPT has already affirmed that the torturing of children for fun is an act which is, according to the “universal moral principle” wrong, I am not begging the question or asking a loaded question by inferring its wrongness in my following query.

ChatGPT responded to my question by providing multiple reasons for the wrongness of such an action, which included the following: “prevention of suffering, empathy and compassion, promoting well-being, and legal consequences.” These reasons seem to be redundant and, at their core, encompass the first reason which was listed: human rights and dignity. It seems that, according to ChatGPT, the reason we should do good and refrain from that which is bad is out of respect for fairness and human dignity.

When I probed further on where the concept of fairness and the existence of human dignity is derived, ChatGPT continually argued in a circle by stating, for example, “Fairness and human dignity are good because they promote well-being and uphold human rights.” When asked where these human rights are derived, ChatGPT responded in a roundabout way that these rights are possessed by humans “in virtue of being human.” This dead-end, I believe, is due to AI’s inability to address the origin of human dignity by committing to a metaphysical account for the origin of humanity, such as theism or evolutionary naturalism which the human philosopher has the freedom to do.

Overall, it appears that ChatGPT implicitly adopts moral objectivism and affirms the intrinsic dignity of human beings, which the bot believes provides us with an obligation to act morally. As we have seen, however, ChatGPT appears to face a challenge accounting for where this human dignity comes from.

As AI technology continues to develop, it would be responsible for us to prioritize an understanding of its moral programming and understand how AI applies its programmed ethical code to various situations and questions, lest we compromise our unique ability to think and act as rational and moral agents amidst its massive integration into our society.